[:en]By Gonçal Calle Rosingana

Our mind is constructed in such a way that it has to make sense of the world that surrounds us. It does so by means of superfast, non-stop, efficient processes that stream inside our heads at speeds that can barely be measured. Everything we see, the movements we make while driving, the words somebody said just five minutes ago, the advertisement on the radio, this same text, and many other hundred things our mind constantly engages in, are mere examples of the frantic activity in our minds. In this state of affairs, economy becomes a crucial strategy to manage the available resources.

This pervasive aspect of our mind has remarkable ways to keep the ship afloat. The concept understand may serve as an example. Concepts emerge in language as tips of icebergs of colossal magnitudes that encapsulate innumerable meanings. The conceptual complexity concealed under the surface is huge but whenever a concept is used, only a little part of its potential will be unfolded.

A dictionary could define the verb understand as ‘perceiving the intended meaning of words, language, or people’, ‘perceiving the explanation or significance of something,’ or ‘our capacity of inferring knowledge from the information we receive,’ to name only a few of its possible meanings and disregarding the myriad possible contexts where it can be used.

However, a point must be raised here. When speakers need to check understanding after making explanations with a certain degree of complexity, they use expressions such as ‘Do you know what I mean?’ with an underlying meaning “Do you understand what I am trying to say?” In other cases, understanding may be conceptualized as ‘sight’ with analogous results; with expressions such as ‘Can you see what I mean?’ or ‘Is it clear?’ simpler scenarios are generated. What the listeners metaphorically see is what they happen to understand. These metaphorical uses are deeply rooted in our minds and widely accepted in our conceptual system.

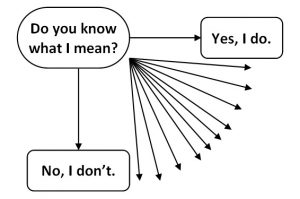

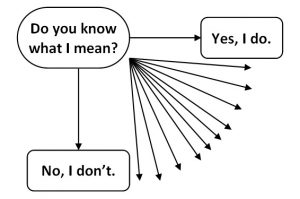

More often than not, though, the answer to the questions above does not fit with the polarised, dichotomous contrast that a ‘Yes, I do.’, or ‘No, I don’t.’ invite us to respond. Very much the opposite. Our understanding drifts towards unspecific middle grounds between these juxtaposed possibilities opening an enormous breach between them.

In most communication acts, the imaginary line that separates understanding from not understanding blurs and widens to the point that the participants in the speech event tend to develop more elaborate replies to define more accurately what their degree of understanding is by adding extra information. Frequently, the speakers end up expressing doubtfulness, or requiring clarification of the most intricate part of the explanation with phrases such as ‘Yes, but ….’ / ‘Not quite. I can’t see…’.

If reality is so constructed and speakers are aware of this, why does language codify ‘understanding’ in such a dichotomous way? This question leads to the beginning of the discussion: the pervasiveness of efficiency and effectiveness by means of the reduction of superfluity. Polarity, solving a problem with a yes/no answer, is an extremely effective compression feature that is aimed at reducing the abstractness involved in certain conceptualizations. In the case of the concept understand, there seems to be a motivated attempt to rule out conflict between the speakers engaged in conversation. This way, speakers have the possibility to dismiss the question with a simple ‘Yes, I do.’ or ‘No, I don’t.’ and, thus, avoid getting bogged down in determining their exact grasp at every stage of the conversation. I hope you know what I mean!

[:ca]Disponible només en anglès

[:ca]Disponible només en anglès

By Gonçal Calle Rosingana

Our mind is constructed in such a way that it has to make sense of the world that surrounds us. It does so by means of superfast, non-stop, efficient processes that stream inside our heads at speeds that can barely be measured. Everything we see, the movements we make while driving, the words somebody said just five minutes ago, the advertisement on the radio, this same text, and many other hundred things our mind constantly engages in, are mere examples of the frantic activity in our minds. In this state of affairs, economy becomes a crucial strategy to manage the available resources.

This pervasive aspect of our mind has remarkable ways to keep the ship afloat. The concept understand may serve as an example. Concepts emerge in language as tips of icebergs of colossal magnitudes that encapsulate innumerable meanings. The conceptual complexity concealed under the surface is huge but whenever a concept is used, only a little part of its potential will be unfolded.

A dictionary could define the verb understand as ‘perceiving the intended meaning of words, language, or people’, ‘perceiving the explanation or significance of something,’ or ‘our capacity of inferring knowledge from the information we receive,’ to name only a few of its possible meanings and disregarding the myriad possible contexts where it can be used.

However, a point must be raised here. When speakers need to check understanding after making explanations with a certain degree of complexity, they use expressions such as ‘Do you know what I mean?’ with an underlying meaning “Do you understand what I am trying to say?” In other cases, understanding may be conceptualized as ‘sight’ with analogous results; with expressions such as ‘Can you see what I mean?’ or ‘Is it clear?’ simpler scenarios are generated. What the listeners metaphorically see is what they happen to understand. These metaphorical uses are deeply rooted in our minds and widely accepted in our conceptual system.

More often than not, though, the answer to the questions above does not fit with the polarised, dichotomous contrast that a ‘Yes, I do.’, or ‘No, I don’t.’ invite us to respond. Very much the opposite. Our understanding drifts towards unspecific middle grounds between these juxtaposed possibilities opening an enormous breach between them.

In most communication acts, the imaginary line that separates understanding from not understanding blurs and widens to the point that the participants in the speech event tend to develop more elaborate replies to define more accurately what their degree of understanding is by adding extra information. Frequently, the speakers end up expressing doubtfulness, or requiring clarification of the most intricate part of the explanation with phrases such as ‘Yes, but ….’ / ‘Not quite. I can’t see…’.

If reality is so constructed and speakers are aware of this, why does language codify ‘understanding’ in such a dichotomous way? This question leads to the beginning of the discussion: the pervasiveness of efficiency and effectiveness by means of the reduction of superfluity. Polarity, solving a problem with a yes/no answer, is an extremely effective compression feature that is aimed at reducing the abstractness involved in certain conceptualizations. In the case of the concept understand, there seems to be a motivated attempt to rule out conflict between the speakers engaged in conversation. This way, speakers have the possibility to dismiss the question with a simple ‘Yes, I do.’ or ‘No, I don’t.’ and, thus, avoid getting bogged down in determining their exact grasp at every stage of the conversation. I hope you know what I mean!

[:es]Disponible solo en inglés

[:es]Disponible solo en inglés

By Gonçal Calle Rosingana

Our mind is constructed in such a way that it has to make sense of the world that surrounds us. It does so by means of superfast, non-stop, efficient processes that stream inside our heads at speeds that can barely be measured. Everything we see, the movements we make while driving, the words somebody said just five minutes ago, the advertisement on the radio, this same text, and many other hundred things our mind constantly engages in, are mere examples of the frantic activity in our minds. In this state of affairs, economy becomes a crucial strategy to manage the available resources.

This pervasive aspect of our mind has remarkable ways to keep the ship afloat. The concept understand may serve as an example. Concepts emerge in language as tips of icebergs of colossal magnitudes that encapsulate innumerable meanings. The conceptual complexity concealed under the surface is huge but whenever a concept is used, only a little part of its potential will be unfolded.

A dictionary could define the verb understand as ‘perceiving the intended meaning of words, language, or people’, ‘perceiving the explanation or significance of something,’ or ‘our capacity of inferring knowledge from the information we receive,’ to name only a few of its possible meanings and disregarding the myriad possible contexts where it can be used.

However, a point must be raised here. When speakers need to check understanding after making explanations with a certain degree of complexity, they use expressions such as ‘Do you know what I mean?’ with an underlying meaning “Do you understand what I am trying to say?” In other cases, understanding may be conceptualized as ‘sight’ with analogous results; with expressions such as ‘Can you see what I mean?’ or ‘Is it clear?’ simpler scenarios are generated. What the listeners metaphorically see is what they happen to understand. These metaphorical uses are deeply rooted in our minds and widely accepted in our conceptual system.

More often than not, though, the answer to the questions above does not fit with the polarised, dichotomous contrast that a ‘Yes, I do.’, or ‘No, I don’t.’ invite us to respond. Very much the opposite. Our understanding drifts towards unspecific middle grounds between these juxtaposed possibilities opening an enormous breach between them.

In most communication acts, the imaginary line that separates understanding from not understanding blurs and widens to the point that the participants in the speech event tend to develop more elaborate replies to define more accurately what their degree of understanding is by adding extra information. Frequently, the speakers end up expressing doubtfulness, or requiring clarification of the most intricate part of the explanation with phrases such as ‘Yes, but ….’ / ‘Not quite. I can’t see…’.

If reality is so constructed and speakers are aware of this, why does language codify ‘understanding’ in such a dichotomous way? This question leads to the beginning of the discussion: the pervasiveness of efficiency and effectiveness by means of the reduction of superfluity. Polarity, solving a problem with a yes/no answer, is an extremely effective compression feature that is aimed at reducing the abstractness involved in certain conceptualizations. In the case of the concept understand, there seems to be a motivated attempt to rule out conflict between the speakers engaged in conversation. This way, speakers have the possibility to dismiss the question with a simple ‘Yes, I do.’ or ‘No, I don’t.’ and, thus, avoid getting bogged down in determining their exact grasp at every stage of the conversation. I hope you know what I mean!